When we discuss ethics with regards to human remains in archaeology and history, we tend to focus on the present, its challenges, its needs, and its sensibilities. How to best care for human remains in museums and research is indeed the fundamental question for Ethical Entanglements. But, what about in the past? How did people in the past feel about opening tombs and graves; how did they practice exhumation, what did they think about it, and what debates surrounded this practice? How can the insight into past experiences, values, and practices, be helpful tools as we encounter historic human remains in the present?

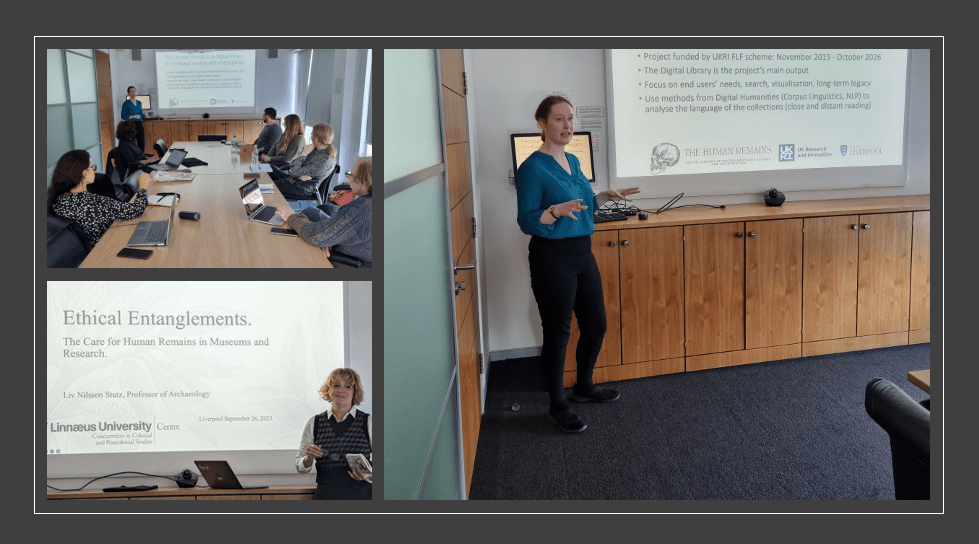

Presentations and discussions with the project teams of The Human Remains and Ethical Entanglements at the University of Liverpool. Photos by Liv Nilsson Stutz and Rita Peyroteo Stjerna.

These questions are central to the research project The Human Remains: Digital Library of British Mortuary Science and Investigation, headed by Ruth Nugent at the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool.

This impressive research project aims at investigating the history of exhumation, investigation, reburial, and recording of human remains from Christian contexts in Britain from the 7th to the 19th century. The project creates a corpus of knowledge and references that will be of great value, both for interdisciplinary academic scholarship for anybody interested in historical practices and attitudes to death, the body, decay, the afterlife, etc – but also as a support for professionals working in contexts where they encounter historical human remains from Christian contexts, including museum professionals, contract archaeologists, and cathedral managers and workers.

On September 26, the Ethical Entanglements Team had the pleasure to spend an afternoon with The Human Remains Team (Ruth Nugent, James Butler, Glenn Cahilly-Bretzin, Katherine Foster, and Thomas Fitzgerald). After a general introduction of the two projects by the PI:s, we launched into a discussion on a range of topics where we found that the two projects share overlapping research interests, including asking what it means to treat human remains “with respect,” and how our research can best support decision makers today in their encounter with human remains – whether it is people working in contract archaeology, cathedrals, or museums. We also discussed how the context may affect the professional ethics and reflection, and what one context can learn from the other. Our conversations explored how to handle contemporary anxieties around human remains, and the elusive yet central concept of “respect” with regards to historic collections and professional ethics.

Left to right: Sarah and Rita in front of the church in Tideswell; Liv and Sarah on the path to the gibbet site at Peter’s Stone – a prominent feature in the landscape of Cressbrook Dale in Derbyshire; Sarah and Rita writing at the cottage in Tideswell. Photos by Liv Nilsson Stutz and Rita Peyroteo Stjerna.

After the visit at the University of Liverpool, the Ethical Entanglements team spent a few days on a writing retreat in the Peak District. Between writing sessions at our small cottage in Tideswell, we made visits to local sites that inspired us to think about several dimensions of past practices. At the the beautiful local church in Tideswell we saw a small but dynamic church community that, as indicated by large fundraising signs posted in the church yard, struggled to make ends meet as they cared for both a living community and a rich cultural heritage. If you are dealing with the considerable financial burden of keeping up your historic church buildings, the care for the dead buried in the church yard, under the floors, and potentially elsewhere, is presumably a factor you must always consider, and one that is not always easily solved. A visit to the historic gibbet site Peter’s Stone in Cressbrook Dale inspired us to think about the historic practice of extending criminal punishment beyond death to affect the corpse through violence and humiliation, a topic Sarah has written extensively about in her book (with Emma Battell Lowman) Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse. While local history and folklore seems to offer different accounts in the details, the corpse of a murderer was gibbeted here after being hanged for the crime of murder. A quote form “Worm Hill – the History of a High Peak Village” by Christopher Drewry sums up the economy of death and punishment, the public spectacle of the gibbeting as meaningful (and popular) cultural practice, and the landscape of dread that would have been at least part of the characteristic of places like these (see also The Landscape of the Gibbet by Sarah Tarlow and Zoe Dyndor 2015):

The costs of this horrendous ritual were not insubstantial – £31-5-3 for the investigation leading up to the arrest; £53-18-8 for the gibbeting and £10-10-0 for the gaoler and escort from Derby to Wardlow. Such was the public fascination with the event however that the vicar of Tideswell found none of his congregation in church on the day of the gibbeting but all of them and more at Wardlow where he took the opportunity of delivering a sermon of fire and brimstone under the gallows. Lingard’s skeleton is alleged to have hung on the Wardlow Mires gibbet in chains until it was finally removed 11 years later on 20th April 1826 after complaints about the gruesome chattering of the bones in the wind. The site of this hanging would have been the so-called Gibbet Field at Wardlow Mires where other hangings are reputed to have taken place earlier, including one of a notorious highwayman called Black Harry who was finally apprehended in Stoney Middleton Dale in the 18th century.

https://derbyshireheritage.co.uk/misc/peters-stone-gibbet-rock-wardlow-mires/

Beyond the contextual, there is something here – something about how despite the fact that gibbeting was a sanctioned cultural practice, also teaches us that even across that cultural divide, there was a line that was being crossed. Deliberately.

In addition to providing a beautiful walk, this place provides a concrete experience to think about the passing of time and the changes in culture, and inspires us to reflect if there is such a thing as an ethical fixed point to provide support as we reflect on what it means to be ethical when handling old human remains.

Featured images: Left: Walking toward Peter’s Stone; and Right: the Red Brick Building at the University of Liverpool, photos by Liv Nilsson Stutz and Rita Peyroteo Stjerna