Should we consider the privacy of people in the past? Is the concept relevant, or applicable? Is privacy only a concern for the living in our contemporary moment – so obsessed by the boundary between the personal and the private in a constantly marketing and sharing economy, or is privacy a more universal human right? What duties do we have to past persons (to paraphrase the excellent PhD thesis by Malin Masterton)?

Woman With Veil – Cleveland Museum of Art (33666109413).jpg” by Tim Evanson from Cleveland Heights, Ohio, USA is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

October 12-13, 2023 Ethical Entanglements participated in a conference at the Center for Privacy Studies at the University of Copenhagen, called Privacy and Death: Past and Present. The conference was interdisciplinary, with contributions from history, classics, archaeology, theology, law, and ethnography, and explored a range of issues touching on the broader issues of privacy and death. Ethical Entanglements contributed with two papers: Nicole Crescesnzi presented the paper: Human Remains and Privacy – a Contemporary Bias? and Liv Nilsson Stutz and Rita Peyroteo Stjerna presented The New Frontiers of Postmortem Privacy: Negotiating the Research Ethics of Human Remains in the Era of the Third Science Revolution in Archaeology.

Left: The organisers of the conference Felicia Fricke and Natacha Klein Käfer welcome the attendants. Right: Rita Peyroteo Stjerna and Nicole Crescenzi before their presentations. Photos by Liv Nilsson Stutz.

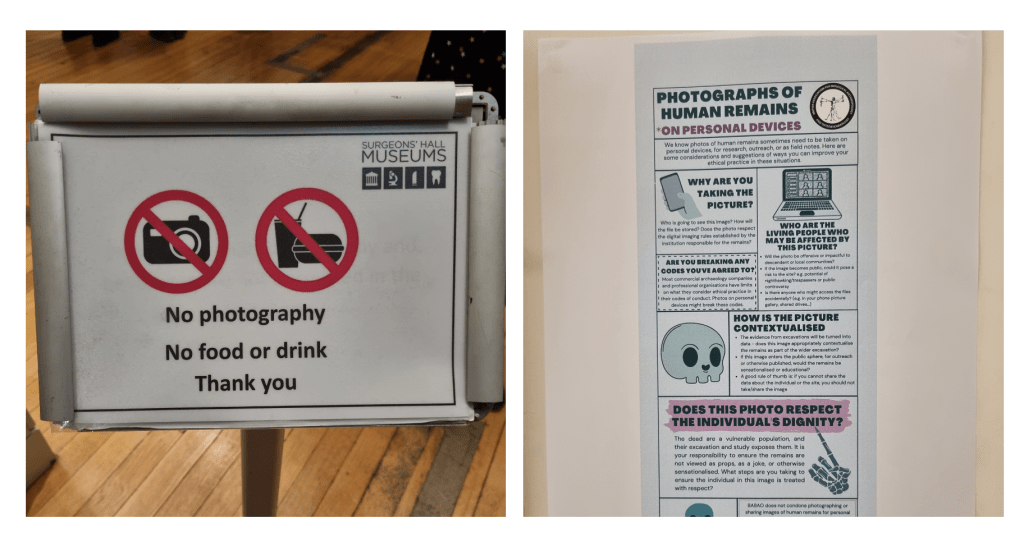

The privacy of old human remains is an issue that tends to lie at the periphery of our debates. There is rarely any explicit discussion about it, but we increasingly see the emergence of professional practices that may indicate a growing consideration, albeit almost invisible. One example of this is how human remains today, sometimes, are blurred in public presentations. If you are a regular reader of this blog, you may have noticed that we also do this from time to time. Another is the signage that is becoming more common, especially in anatomical and pathological exhibitions, of a no photography policy. It is quite possible that there are multiple reasons for this, and it is rarely explicitly stated that this is to protect the privacy of the dead, but it speaks of an awakening sensibility. In some rare cases, as shown below (right) in the signage at the Anatomical Museum at the University of Edinburgh, the sign elaborates on the reason, and in the process, it triggers reflection and raises awareness. In this context it is an explicit and integrated part of the university training of future professionals working in the field, but perhaps this would be useful also in more public exhibitions.

Signeage restricting photography of human remains. Left: at Surgeon’s Hall in Edinburgh, and Right: in the Anatomical Museum at the University of Edinburgh. Photos by Liv Nilsson Stutz.

These types of signs are much more rare, and perhaps even non existent in archaeological exhibitions, demonstrating yet again the gradual move on the spectrum of lived life toward object of science with the age, state of preservation, and disciplinary categorisation of the specimen. Sometimes a sense of respect and dignity is alluded to in the ways in which the human remains are exhibited also in archaeological museums, for example through separation to a reserved space, and dimmed lighting. However, the topic is very rarely addressed head on, and if anybody’s sensitivities are considered in archaeological and historic exhibitions, it is in general the contemporary visitor’s. Nicole Crescenzi’s work on the public’s reception of these types of exhibitions across Europe shows that there are multiple ways in which the exhibition is experienced.

The conference raised many important issues, and several fascinating talks on topics from problematic collections to contemporary mourning practices, that all led to stimulating discussions. For Ethical Entanglements is was especially interesting to see the overlaps of concerns and shared challenges in the keynote address by legal scholar Edina Harbinja entitled An Uneasy Relationship Between Post-mortem Privacy and the Law. She defines post-mortem privacy broadly as the right of a person to preserve and control what becomes of his or her reputation, dignity, secrets, or memory, after death (see also Edwards and Harbinja 2013). While Dr Harbinja’s work is focused on the contemporary digital world, the fundamental questions it raises concern, in our opinion, also the long dead and research ethics in our fields. She proceeded to introducing the term of post-mortal privacy which protects informatised bodies expressed, stored, mediated, and curated through technology – as an immortality by proxy. In our contemporary world this refers to images shared and data stored online and in cloud services and on platforms held by private companies. But, what about the research data we extract from old human remains and share as part of our research activities? These issues relate immediately to the presentation by Liv Nilsson Stutz and Rita Peyroteo Stjerna on the attitudes to postmortem privacy in bio-molecular archaeology, and where Rita’s work, collecting data through interviews with scientists working in the fields, shows both a need and a desire for more thorough professional ethical development in this emerging and constantly changing field.

Can we turn the key to protect private data from spreading – and if we do, does that not violate standards for good scientific practice?

Can we turn the key to protect private data from spreading – and if we do, does that not violate standards for good scientific practice? The challenge, of course, is to determine what such a new practice might look like. With multiple ethics at stake, and with best practices sometimes in complete conflict with one another – for example Open Data vs respect for post-mortem/post-mortal privacy, the challenge is complex. Ultimately we come back to the same question: who still counts as a person enough to deserve this kind of consideration. The answer is not obvious.

“Privacy” by rpongsaj is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The work also has interesting relevance for thinking about museums. Through her research, Dr Harbinja could see that a lot of the progress to think through and identify solutions on behalf of social media platforms such as Facebook, with regards to post-mortem privacy, emerged ad hoc. Somebody in the company started to think about this as they experienced the death of a client who was also a loved one – for example a parent. It struck me that there is a similarity here between the social media giants and museums: they both store sensitive and valuable things, they have inward facing and outward facing responisbilities, and – they both react ad hoc. It is a learning process, but it is also one that in the very moment teaches you to be better prepared the next time if you want to be able to serve your stakeholders well.

Featured image: “PRIVATE NO ENTRY” by Brad Higham is licensed under CC BY 2.0.