Viewed from the outside, it often seems as if the Nordic countries are very similar in terms of culture and values. But despite their entangled political and cultural histories, and their cultural similarities, a closer look reveals interesting differences, and this is certainly the case for their professional attitudes to the ethics of collections of human remains.

The Nordic Network for Collections of Human Remains is an informal forum that organises different stakeholders in human remains collections, predominantly collection managers, but also researchers and museum professionals across the Nordic countries . The purpose of the forum is to provide a space for reflection and support in professional discussions and development of ethical practices. The Network organised a conference at Arkivcenter Syd, in Lund on October 26-27, 2023 (for full disclosure, Liv Nilsson Stutz has been a member of the steering group during the period 2020-2023, and was part of the organising committee for this conference). The purpose of the conference was to come together for the first time after the end of the pandemic, update one another on the state of the field in the different Nordic Countries, and strengthen both formal and informal ties and relationships throughout the community.

The conference invited speakers from several large collections across the Nordic countries to share their perspectives and experiences. Unfortunately the participant from Norway (Julia Kotthaus from De Schreinerske samlinger, at the Medical Faculty at the University of Oslo) had to cancel last minute, since she needed to prioritise her presence at a repatriation from the collection she manages. These presentations were inspiring in the sharing of protocols and experiences, but also showed the differences in approaches between countries.

The Danish model is interesting since it clearly separates ownership from deposition and curation. The former is held by local museums, while the latter is managed by essentially two centralized collections: ABDOU at the University of Southern Denmark (presented by Dorthe Dangvard Pedersen), and The human skeletal collection at the University of Copenhagen (presented by Niels Lynnerup, Marie Louise Jørkov, and Kurt Kjaer). This arrangement has interesting consequences for the management of processes. The facilities are all highly adapted for the preservation and study of human remains, and the research facilities support, track and assist in access to the collection by researchers, students, and even the public. It can be argued that this system that separates the human remains from their otherwise historical and archaeological context in order to prioritise preservation, control, and documentation, implicitly or explicitly categorises the remains almost exclusively as Objects of Science. It appears to be a very clear, but also unproblematising approach. The division has interesting consequences for the most significant case of repatriation of human remains in Denmark, Utimut – the repatriation of human remains and culturally significant objects to Greenland. The ownership of the human remains is now held by Greenland, but Greenland has elected to follow the same system for the management of collections of their human remains as that practiced for remains found on Danish soil, keeping them in Copenhagen. This case is always interesting to bring up in debates about repatriation since it is clear here that the Greenland side appears to share the same concerns for these remains as their Danish counterpart, and also feels that a practice that protects them as Objects of Science is valuable for them. But that does not mean that nothing has changed. There is a significant shift in the attitudes on behalf of the collection managers who do not claim control or ownership, but take the role as mediators and assistants. In this sense then, the Danish system is arguably more inclusive and progressive than in the rest of the Nordic countries, where ownership tends to be associated with the institution that holds the remains.

The Swedish system with decentralised practices and control was illustrated by presentations from two Swedish collections. The Historical Museum at Lund University was represented by Jenny Bergman and Sara Virkelyst who presented a newly established flow chart to systematically support repatriation processes in order to make them transparent and predictable for all stakeholders. The collections at the National Historical Museums were presented by Elin Ahlin Sundman. The issues of ethics appear to be top of mind for the Swedish institutions, but the decentralised practices result in great diversity in protocols and processes – which stands out as quite a contrast to Denmark.

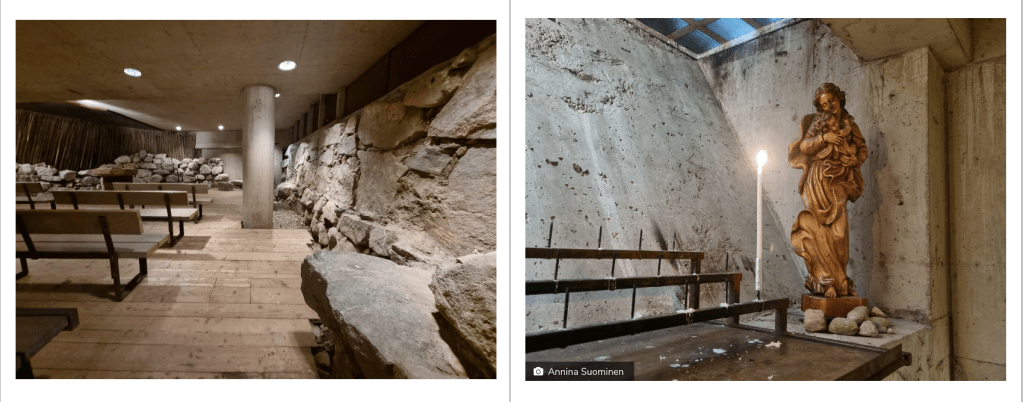

Finland seems to have the least regulation and formalised processes for the care of collections of human remain at the moment. With a law that currently calls for decisions of future reburial to be made before an excavation has even started, human remains, in Finland, appear to be treated more toward the end of “Lived Lives” than in the other countries. They are often reburied immediately – sometimes even before osteological study. It should be added, however, that this position in reality is almost directly dependent on the chronological age of the remains, with prehistoric remains being systematically collected, and historical remains more often reburied. The decision is often made by local parishes who hold a lot of the power in these negotiations. Liisa Seppänen from the University of Turku presented a hybrid solution with the case of the contemporary chapel in the Casagrande House in Turku. The historic building, previously known as Ingmanska huset, was built in the 17th century at the previous location of a Graveyard of the Holy Ghost Church in Turku. After being threatened with demolition in the 1980s, the architect Benito Casagrande purchased and renovated the building under supervision of the Finnish Heritage Agency, and it now includes businesses, shops, and restaurants. The remains of the people buried in the underlying churchyard (from the 14th century and to 1650) were excavated in consecutive projects from the 1960s and through the 1980s, and were collected by a dentist at the university who kept them as a teaching and research collection (predominantly the crania). After extensive lobbying, Benito Casagrande, managed to have the remains transferred from the university to a newly built chapel in the basement of the house, where they can both rest in a sacred space and be accessible for research. The chapel is not open to the public, but can be visited upon request. A small working group, of which Casagrande is a part, oversees the collection and makes decisions with regards to access and curation. The impact of a private citizen is, to say the least, quite extraordinary in this case – but perhaps this is not as difficult to reconcile in a system with a tradition of consultation with the leadership of local parishes. From a more traditional collection manager point of view, Risto Väinölä discussed he human remains collection at the University of Helsinki (LOUMUS) which is a heterogenous collection with a long and diverse history of collection, with potential for research but with limited manifested interest both on behalf of researchers and calls for repatriation.

In addition to the presentations of the state of the field in the respective countries, I also want to highlight two more conceptual papers. Karin Tybjerg from Medicinsk Museion in Copenhagen presented an interesting paper on historical medical collections as a foundation for amemnesis – the clinical medical process of recovering the medical history, usually referring to patient history, to understand medical states in the present, but here expanded to include a broader investigation into the field of medical science, medical history and medical humanities (she has published these ideas in an interesting paper in Centaurus 65(2), in 2023). Equally interesting was Eli Kristine Økland Hausken‘s paper Adressing Bare Bones and Human Remains about her work with exhibitions at the University Museum of Bergen and the underlying ethos of their activities to engage the local community by “lifting the curtain” on the process knowledge production and the history of institutions. I was somewhat surprised at the choice to exhibit a shrunken head, a South American Tsansta (an issue that has also been debated by curator Åshild Sunde Feyling Thorsen from the same intitution), and while I am personally not convinced, I was interested in the arguments in favour of making such an unconventional choice today.

During the course of the conference, three panel talks explored several fundamental issues for the care of collections of human remains. The following topics were explored:

- Panel 1: What is the value of collections of human remains? This panel explored the broader topic of the value of these collections for science, pedagogy and history in a time when they are increasingly questioned. Are they valuable? And if so, how?

- Panel 2: How to make the collections accessible (including perspectives on digitalization, exhibition, and access for researchers). Should we? And how best to do this?

- Panel 3: Accession and deaccession. What are our current challenges? This panel talk will discuss the responsibility (and cost) of accession and deaccession, and discuss the connections to repatriation and (re)burial.

Throughout these conversations it became clear just how entangled these issues really are. The final discussion, on accession and deaccession, also linked up the the local history of anatomy in Lund where a large part of the old and seemingly “worthless” or “problematic” collections from the Department of Anatomy were unceremoniously discarded in 1995 when the department was closed down permanently. Some remains were transferred to the Historical museum (the institution that received most of the skeletal remains) and to other institutions that had previous ownership of remains in the collection, but a shocking amount of wet specimen, ended up in containers to be destroyed or haphazardly collected from the street by private people, potentially to take on another life, now even more in the shadows and even further removed from ethical care. The date, 1995, serves as a reminder that it is not that long ago that these issues were hardly problematised at all.

Featured image: Poster for the General Art and Industry Exhibition in Stockholm 1897 (licensed CC BY-SA 4.0). While this poster from the 19th century shows a different political reality, it can be veiwed as a good illustration of the continued entanglement of the Nordic nation states.