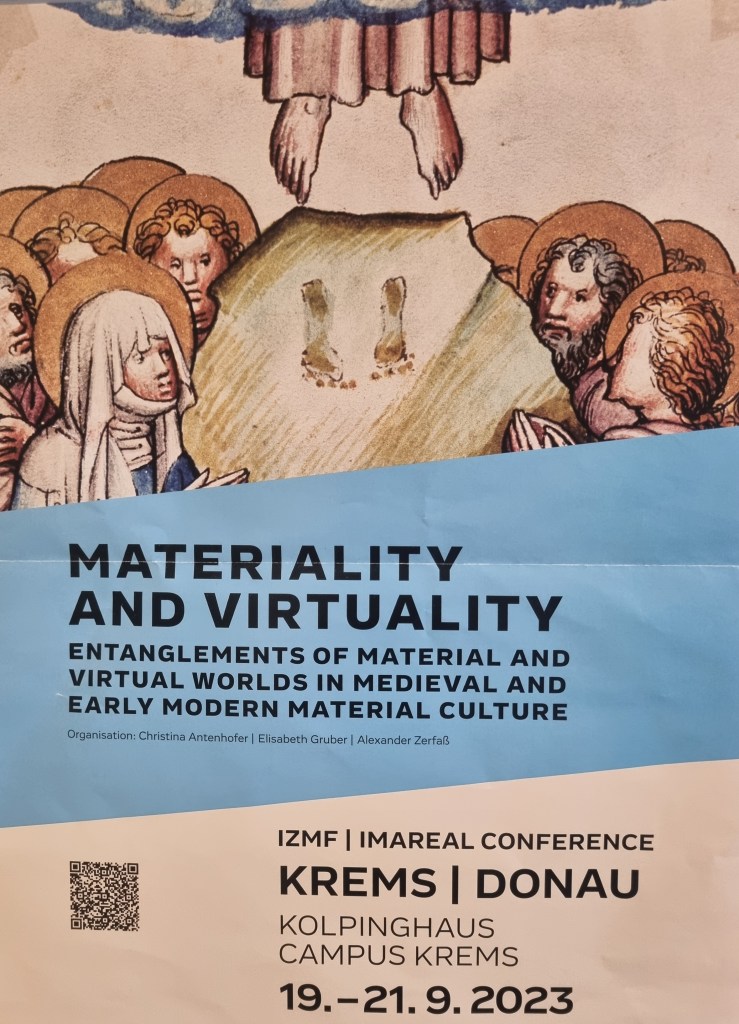

This past week (Sept 19-21, 2023) I had the pleasure to assist at a conference in Krems, Austria, called “Materiality and Virtuality. Entanglements of material and virtual worlds in medieval and early modern material culture,” hosted by IMAREAL (The Institute for Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture). The research centre applies a research perspective they call “Sensing Materiality and Virtuality” as they focus on cosmological realms of the past, such as the German-language afterlife journeys of the High and Late Middle Ages, and “the thought form of the virtual and its interaction with the materiality and sensuality of the body and world.”

One basic principle of this approach is the Aristotelian meaning of virtuality as “capacity” or ‘”dynamis” that does not come to action, but nevertheless has an effect on reality.

“The virtual is not physically present, but it is ‘seemingly real’ (being a simulation that has real effects). It is not material, but nevertheless existent – the latter distinguishes it from fiction. The virtual has real effects, because it refers as potentiality to its actualization and is effective in this reference.”

IMAREAL

To clarify their position, IMAREAL uses the mirror as paradigm: here the virtual unfolds on the surface of the material – the reflection is the result of causal interactions at the material level. And while the virtual only unfolds on the surface of the material, it has real effects “because we actualize it on the reflecting body.”

“I sure am good looking in my pajamas … Vintage Picture of a Cute Young Boy Looking at His Reflection in the Mirror” by Beverly & Pack is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

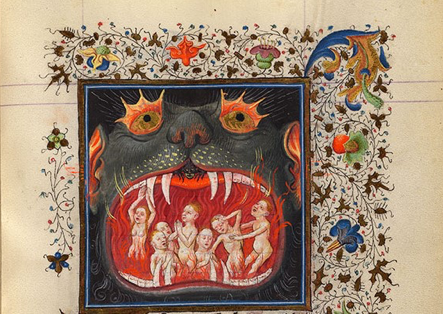

IMAREAL argues that this property – dynamis – capacity and ability to move, did not enter the world with postmodernism and contemporary virtual reality technology, but has probably always been a part of human culture, and one that can definitively be traced in medieval artwork, architecture, and material culture. In a medieval world, and in particular when considering the afterlife, the concept of the body/soul, creates an interesting paradox. The afterlife journey, potentially including heaven, hell, and purgatory, are transcendentary – not conceived of as material, but with long lasting effect on reality, and it is undertaken by the double corporeality of the dead – the physical remains, buried in the ground and left on earth, and the avatar soul that wanders on into the afterlife. Central to this world view however, is the soul’s maintenance of a certain corporeality – one that can be tortured in purgatory and burn in hell. The soul is thus not completely shedding its metaphorical skin – the avatar is a virtual, and while it no longer is understood as material, it still has “the capacity of the corporeal” (e.g. in the sensation of pain).

The immaterial soul/body that can still feel pain. Illustrated by Medieval Hellmouth 1. Cropped image of MS M.917/945, p. 180–f. 97r in The Hours of Catherine of Cleves.

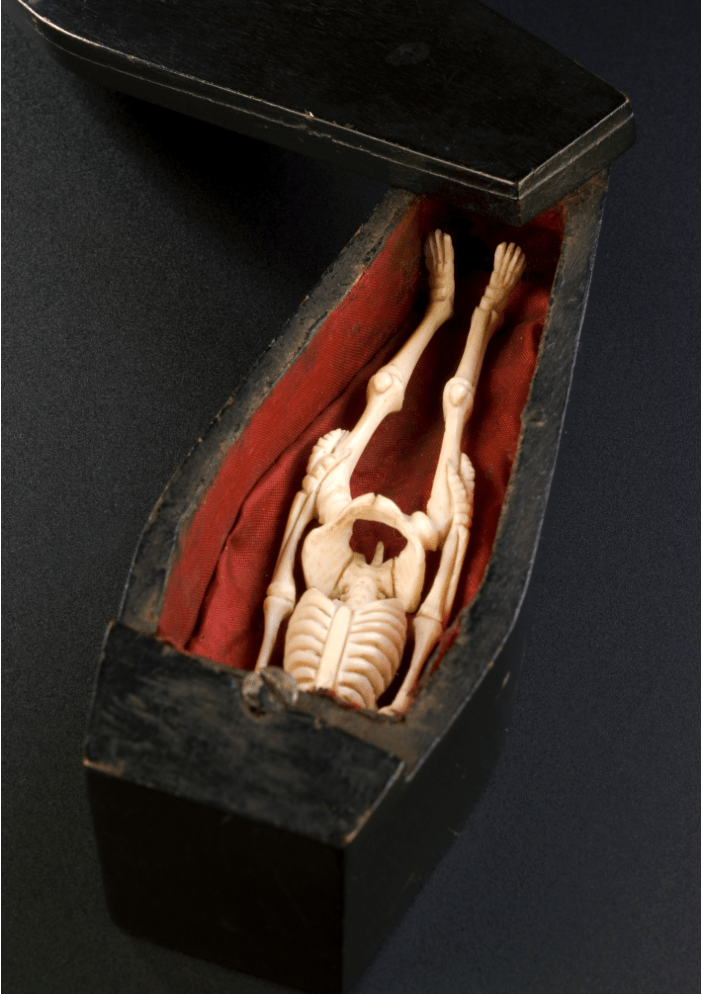

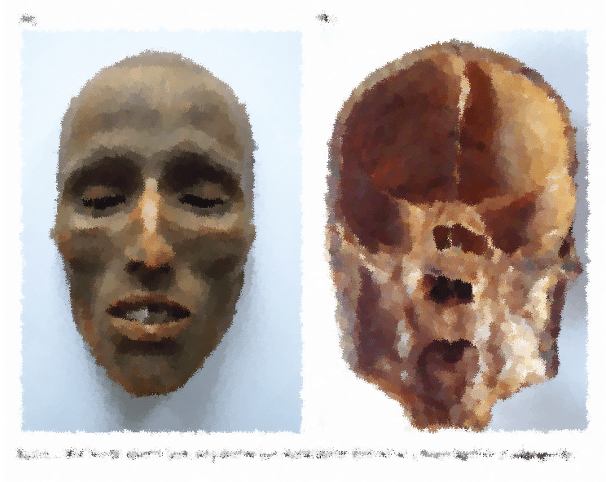

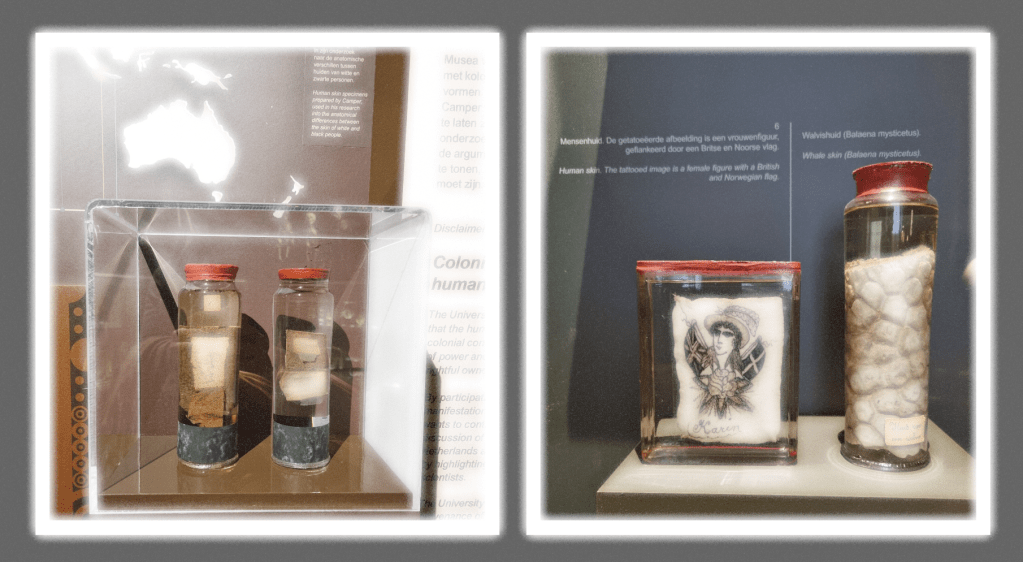

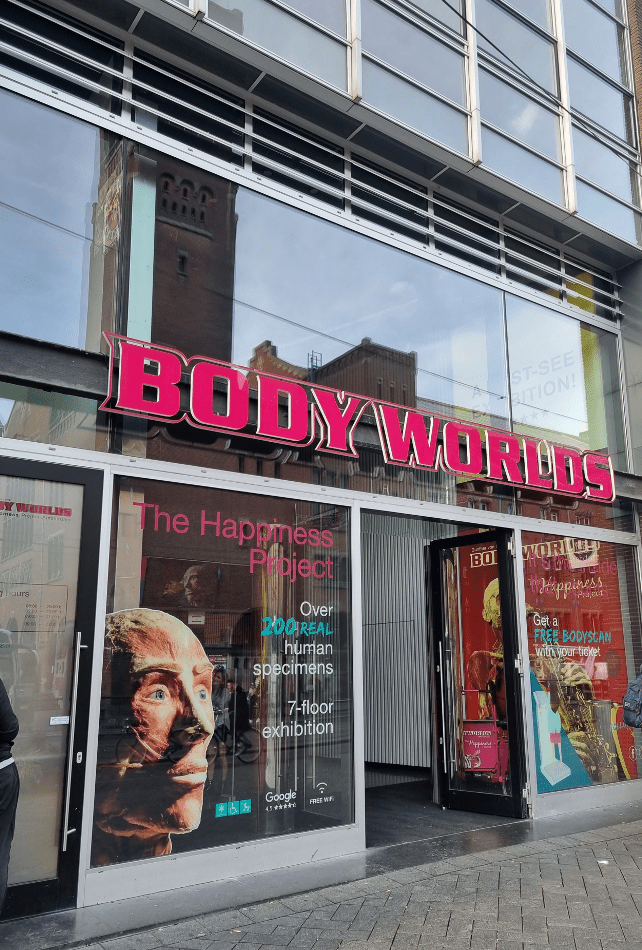

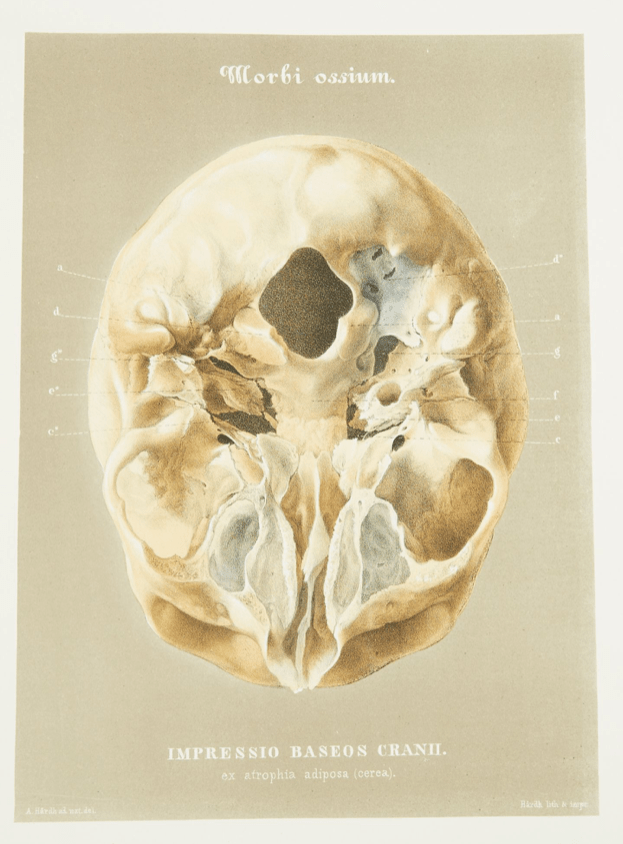

When relating this to research ethics and human remains, it strikes me that the complex nature of the cultural understanding of the human body that we encounter in the debates about research ethics and reburial, resonates with this framework of entanglement between the virtual and the material. The dead body is simultaneoulsy striking in its materiality and the embodiment of a lived life. The virtual emerges from the surface of the bones (or other materiality). This is where the ethical dilemma presents itself as we seek to understand how to best care for them. We wonder if the human remains on the shelves in the museum storage still feel something – if they experience limbo and displacement. If they would consent to being there.

“Questions relating to subject and object, to their distinction and their union, should be put in terms of time, rather than of space”

henri bergson, matter and memory

Bergson’s idea of the relationship between the material and the virtual departs from the neural capacity of the human body, with the nervous system as a “material symbol” of the inner energy we call memory. The capacity for memory allows for humans to depart from their here and now, and in a way extricate themselves for a period of time. Although Bergson does not elaborate on rituals specifically, it appears that this model of the virtual can be connected to Catherine Bell’s concept of ritualisation as a strategic way to act to, in a sense, fire up a connectedness to the overall structure – a continuous whole, which in a Bergsonian sense is a continuity of material extensity in which each individual moves as connected parts of a whole. Yet, we as individuals also function in a time space continuum and through material bodies, and hence the material and the virtual is situated in time and connected to memory.

Building on Bergson, Deleuze elaborated on the term of virtuality, bringing it into closer contact with the real, arguing that it is an aspect of reality that is ideal, but nonetheless real. The virtual is thus not opposed to the real, but opposed to the “actual.” The “real,” he argued, is opposed to the “possible,” thus introducing a movement toward possible realisations, through the concept of duration.

While the conjoined twins previously on display at the Museum of Natural History in Gothenburg (and subsequently cremated) may not actually have felt anything, our encounter with their materiality moves us, and triggers associations in us that enters into a virtuality in which they do. Photo published by Swedish radio and intentionally blurred for this blog.

I am not a philosopher, and I no doubt simplify these complex thoughts in absurdum, but what I take form this is that the idea of elaborating with the connections between the virtual and the material may be fertile ground for further critical examination of the category “old human remains,” as situated in the space between the material and the virtual, between the object and the subject, between the past and the present. In this liminal space lies a multitude of dimensions to explore. To bring the issue back to a series of immediate and concrete challenges, this framework could be valuable as we explore the complexities of 3D-reproductions for display and researech. The relationship between the materiality of the original and the materiality of the copy passes through a digital and virtual space – like the metaphoric mirror, yet enters back into a the world in a materiality that potentially prompts all the ethical issues embedded in the original and authentic specimen – with added dimensions of ownership and control, no longer only of the original, but of the copy as well. But the concepts of virtuality and materiality also brings us back to the foundational questions of the project:

- does the age of old human remains affect the relationship between the subject and the object?

- can the materiality of the human remains ever be separated froheorym the virtuality that unfolds from our encounter with them, and to what extent is can this virtuality be separated from the cultural context of the encounter? Is there such a thing as an invariably essential virtuality, or can it only emerge in each encounter, making it potentially endlessly variable?

- To what extent do we all feel compelled to enter into contact with the virtual as we encounter the materiality of human remains? Are they inhabited by some sort of universal quality that in this respect, transcends cultural difference?

Featured image: the body of Christ. Piarist Church of Our Lady, Krems. Photo by Liv Nilsson Stutz