On our way to the EAA meetings in Rome, the Ethical Entanglements team stopped over in Bolzano to see the exhibit of one of the most famous individuals in European prehistory, “Ötzi the Ice Man,” at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, and to meet with the director Elisabeth Vallazza to discuss choices, strategies, and experiences in caring for such an exceptional individual. The visit proved to be very interesting since not only the archaeological find itself, but also the choices for the display, are unique, and inspire reflection and discussion.

In 1991 two hikers found the remains of a human body, emerging from the melting ice in the Ötzal Alps, on the border between Italy and Austria, at an altitude of 3,210 meters. The body was so well preserved that it was assumed to be the remains of a recently deceased mountaineer, and local rescue and law enforcement were alerted. The body, still partially encased in the glacier, was pried from the ice with force. The working conditions were difficult because of dire weather conditions and the process was delayed. The body, along with objects recovered at the site, were eventually transported to the medical examiner’s office in Innsbruck. There, archaeologist Konrad Spindler concluded that this was not the body of an unfortunate alpinist, but an individual from the end of the Neolithic period. Closer examination of the human remains would later reveal that he had been the subject of two violent attacks before his death. First an encounter several days earlier, that led to a stabbing wound in his hand. Then an attack by arrow, causing both severe damage to his shoulder and blood loss, and leaving the arrowhead lodged in his shoulder.

The find soon captured global attention from archaeologists and the public alike. The body was given the name Ötzi, and as science uncovered details about his life and death, his humanity emerged and captured the attention of a large public. He soon became one of the best-known individuals of European prehistory. When we visited the museum on a Monday morning in late August, people were lining up in a long queue that spilled out into the street and around the corner of the museum. Droves of people waited patiently in the light summer rain. They were all there to see Ötzi.

The find is spectacular. The naturally mummified body has allowed for a range of studies that have provided insight into his cause of death, his diet, his movements thoughout his lifetime, his health status, and his tattoos. In addition to the body itself, Ötzi’s clothes and gear provide a unique window into a dimension of stone age material culture that is rarely preserved. His coat carefully crafted from alternating pelts of goat and sheep skin creating a striped garment, is stunning, as are his leggings made from small patches of goat skin carefully sewn together in a patchwork pattern, and his shoes padded with dried grass. His toolkit includes, among other things, birchbark vessels, a fire kit of embers wrapped in leaves, a bag pack, a perfectly preserved mounted copper axe, and a soft hammer composite tool with a cylindrically shaped core made of deer antler placed in the centre of a wooden handle.

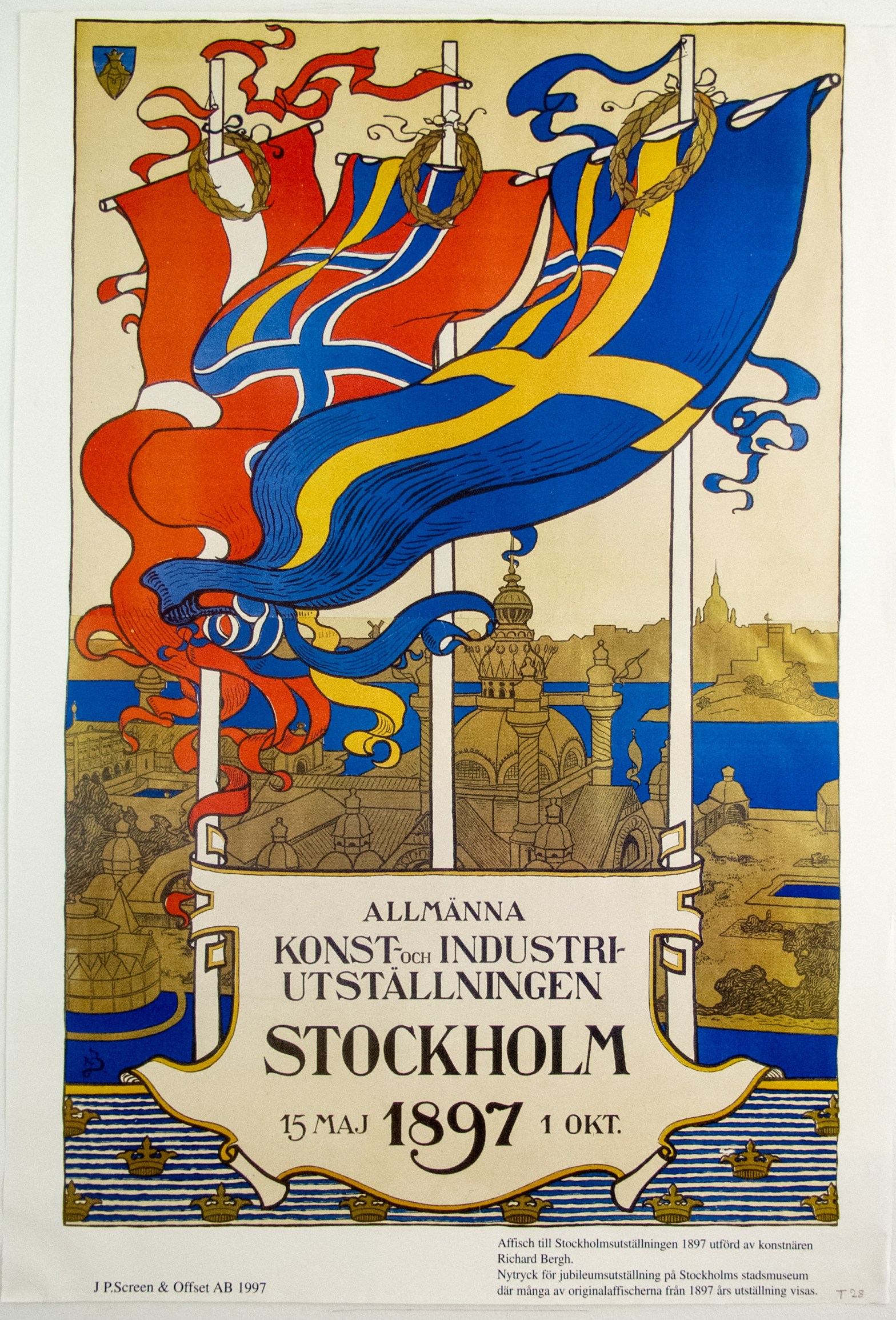

When Ötzi was found in 1999, the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology was still just in the planning stages, but the find (and presumably the much-covered border dispute regarding the national claim to the find) prompted an acceleration of the plans, and in 1999 the museum could open with an exhibition centered on these extraordinary finds. How, we wondered, do you curate and care for Ötzi and his artefacts? How do you tell his story, that is so connected to him as an individual, to the public today? What can you show – and how? Bolzano is a town in a conservative region, and there were initially some objections from traditional Catholics about showing the body of a dead person. But the museum decided nevertheless to put Ötzi on display for visitors to see.

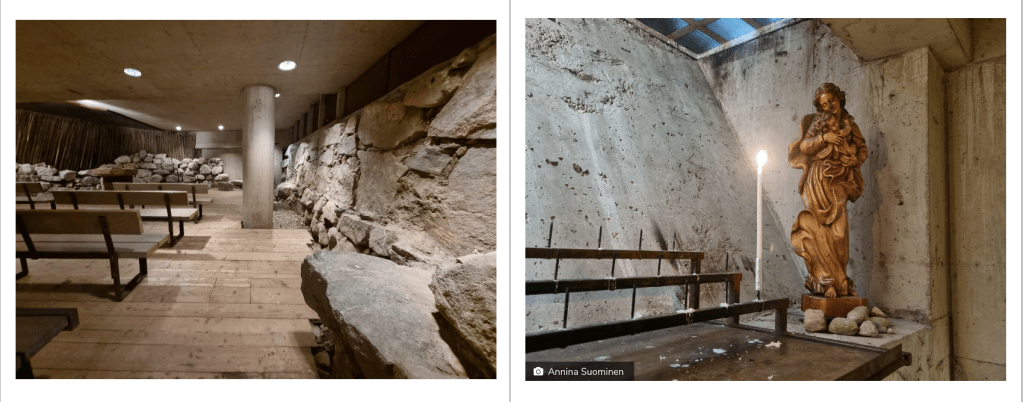

The way the museum shows Ötzi is an interesting example of how conservation can be combined with a pedagogical experience for the public. The conservation needs call for a stable environment of -6°C, and to make this possible, Ötzi is placed in a controlled and protected space with limited exposure. The walls protecting him are clad in metal and give off an almost fortresslike vibe. But despite the coldness of the space, the needs to protect and preserve have created a display that in addition to providing an optimal environment for preservation, also guides the visitor to a personal encounter.

The area where the body is on display is shielded off by a convex screen wall, and behind it a short maze created by retractable barriers allows visitors to stand in an orderly line gradually approaching the metal clad wall with a small square window into which one person at the time can look at Ötzi. The queuing system, and the one-to-one encounter may just be the fortuitous result of preservation requirements, but it provides an experience during which each visitor has a period of waiting, a period that allows them to pause and prepare themselves for the privilege of meeting an individual from the deep past. The small window frames the encounter itself to be one of equality. The set up focuses your attention to the window and prevents, or at least hinders conversations among visitors during the meeting. It becomes focused – even personal. When we visited Ötzi we were alone in the museum, and the scene was quiet. As we walked past it later that morning after the museum had opened to the public, the area was a lot louder and more busy – but the short moment of encounter would still provide the opportunity to focused attention – even contemplation.

…it is interesting to note that the body itself is so central to how we understand Ötzi. It is his naked body that people associate with the find. It is the image of the mummified remains –with the left arm in extension, rotated inward and lifted across the body–we most often see on book covers and websites. It is also very likely that it is this body that most of the visitors are there to see.

When asked about people’s reactions to the display, Elisabeth Valazza shares that the great majority of the feedback they get is positive, even emotional, but rarely critical or negative. It seems like the exhibition choice is successful. There are no trigger warnings or special instructions to the visitors (except that photography is not allowed). It appears that the embodied experience (the waiting in line, the one-to-one encounter) may serve the purpose of reframing the visit in a more fundamental way that makes these direct communications unnecessary. Of course, we cannot know for sure since we did not interact with the visitors about their experience, but it seemed like a real possibility.

Ötzi’s body is displayed without clothes. This is partially a preservation choice. Different materials require different forms of conservation and care. Here the choices made clearly privilege conservation and even accessible exhibition over, for example, respect for the dead. Given the exceptional character of the objects and the mission of museums to preserve them, this is not surprising. But it is interesting to note that the body itself is so central to how we understand Ötzi. It is his naked body that people associate with the find. It is the image of the mummified remains – with the left arm in extension, rotated inward and lifted across the body – we most often see on book covers and websites. It is also very likely that it is this body that most of the visitors are there to see. Elisabeth Vallazza shared an anecdote that illustrates this. One day the lighting in the window display stopped working and the staff started to problem solve. Would they have to reimburse the visitors if they were not able to see Ötzi? The fact that the museum was filled with unique artefacts somehow did not immediately seem enough. The body is important.

The impact of Ötzi’s naked body – so fragile, small, and stripped – is, at least for me, one of vulnerability. This vulnerability can be contemplative for the visitor – it may allow them to see Ötzi as a vulnerable human in death, or perhaps themselves, or mortality, at that private privileged moment at the window. But, of course, the ethical issues remain entangled. Is it right to show him this way? Are there any alternatives?

The reconstruction of Ötzi is also very telling. In a room dedicated to the reconstruction, he is on display holding his partially finished bow, and wearing his underwear and leggings – but with his upper body bare. The reason given for this is that it was important to show the tattoos on his back. It is interesting that these tattoos are considered more important and more interesting, than, for example the coat – or the full gear. This makes me wonder about our fascination with mummified bodies as rare, and somehow intriguing in and of themselves to the point of overriding other interests. This is especially obvious at the mummy table where visitors can touch an interactive screen and digitally unpeel the layers of his body. This feature stands in very stark contrast to the structured visitation of Ötzi at the square window.

For the most part the museum display of Ötzi shows him more as a lived life than as an object of science. A lot of room is dedicated to telling the story about his life and death. A parallel narrative throughout the exhibition is that this lived life emerges from the scientific work carried out on both his body and the material culture found with him – as objects of science. Here the two are intimately linked and dependent on one another. The close connection with the museum to this one exceptional individual seems to have created a sort of “bond of care.” This is a phenomenon I have noted elsewhere in museums that have singular, but exceptional human remains. Somehow their uniqueness (in character and quantity) favours care. However, because of Ötzi’s celebrity status, not only his objects, but especially the reconstructions of his body now exist in multiple copies in different museums across the world. What happens to the care for his personhood as his body transitions through versions of virtuality and materiality – at the mummy table and through replicas of his body throughout the world? Is this something we need to consider?