The European Association of Archaeologists convened at Queens University in Belfast for their annual meeting, August 30th to September 2nd, 2023.

Conference mood. Photo: Liv Nilsson Stutz

Two events immediately touched on the ethical dimensions of human remains, and Ethical Entanglements was present at both of them. The first was a session entitled “From What Things Are to What They Ought to Be: Ethical Concerns on Archaeological and Forensic human remains, organized by Clara Viega-Rila, Angela Silva-Bessa, and Marta Colmenares-Prado. The session included 11 papers with contents ranging from the ethical considerations at the the molecular level of human remains, to the ethics of repatriation, museum practices and contract archaeology.

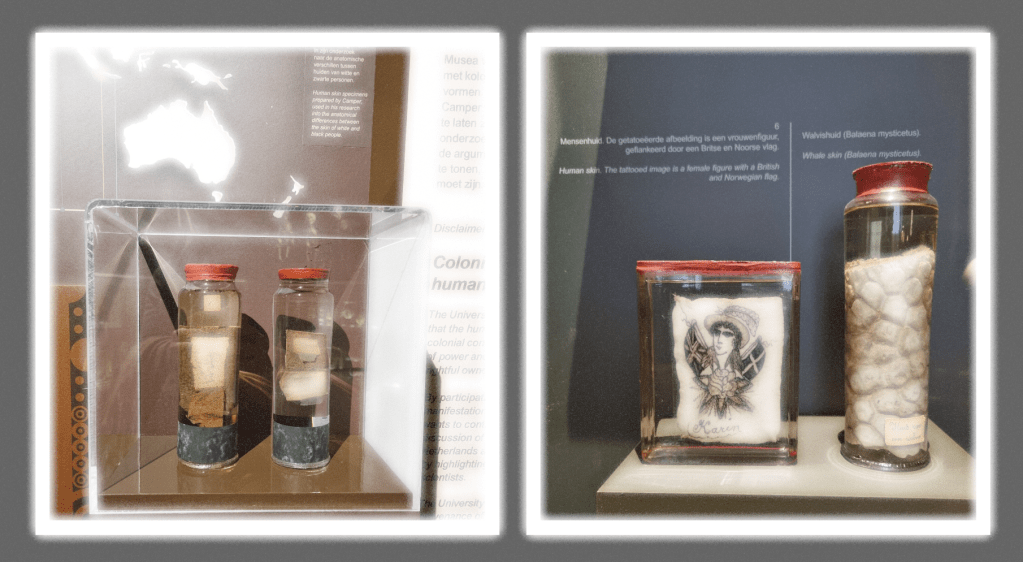

Aoife Sutton- Butler discussed her survey of visitors to museums with anatomical and pathological collections with regards to “potted specimen.” The survey demonstrated that an overwhelming majority of people tend to both accept and value the opportunity of viewing these human remains on display. The general representation of the study can be discussed since it only included people who had elected to visit these museums, but among the interesting insights was that many said that the experience allowed them to identify with the the person in the past – thus challenging assumptions often made that potted specimen automatically are a form of objectification. An interesting detail in the study was that the use of potted specimen in teaching helped students in osteology to think more carefully and intentionally about the personhood of the individual, and about pain and suffering.

Example of “potted specimen” [File:Fig-1-Photograph-of-the-teratological-collection-in-the-Museum-for-Anatomy-and-Pathology-of-the-Radboud-University-Medic.gif, by Lucas L. Boer, A. N. Schepens-Franke, J. J. A. Asten, D. G. H. Bosboom, K. Kamphuis-van Ulzen, T. L. Kozicz, D. J. Ruiter, R-J. Oostra, W. M. Klein is licensed under CC BY 4.0.]

Constanze Schattke and colleagues form the Natural History Museum in Vienna presented another study that looked at public opinion, in this case with regards to repatriation of human remains from non-European contexts. Their approach to the topic was to analyse newspaper articlas and their online comments section, and code pro and con attitudes. They concluded that while there is are still different views on the topic, over all, the public is more positive to the repatriation of human remains than to the return of objects, which indicates – once again, that human remains are not perceived as neutral objects.

In her thoughtful and problematising paper “Sentenced to Display,” Ethical Entanglements member Sarah Tarlow prompted the room to question the ethics of the display of the human remains of known historic criminals. While the encounter with these infamous bodies in surrounded by a certain level of glamour and thrill, we must also ask to what extent the display of these bodies in museums today simply prolongs the abandoned practice of punishment by display.

I (Liv Nilsson Stutz) presented a paper – “Handling Liminality” – on the results of the survey of the handling of human remains in Swedish museums (also recently published in the International Journal of Heritage Studies) with a focus on the theoretic model of viewing old human remains on a spectrum between objects of science and lived lives.

Ethical Entanglements member Rita Peyroteo Stjerna presented a thought provoking paper entitled “The Multiple Ethics of Biomolecular Research on Human Remains: Researcher’s Perspective” on the emerging ethical challenges relating to the new methods for analysis often associated with the Third Science Revolution in Archaeology – including issues relating to the privacy of the dead, the unbalanced relationship in knowledge production, and curation and preservation. Her paper presented insights gleaned from interviews with laboratory based scientists, and advocated for the a more proactive engagement with the development of professional ethics that also includes these researchers in the conversation.

Ina Thegen and Clara Viega-Rilo both addressed the challenges of contract archaeology in Denmark and Spain respectively, with lessons learned and thoughts about and how to best engage with multiple and embedded stakeholders including the public, the media, descending communities, and communities of faith.

Three papers engaged in different ways with the legal regulation and process of professional ethics. Sean Denham presented the Norwegian model where research on old human remains, and while recognising the multi-disciplinary character of the research, is included under the broader umbrella of the National Research Ethics Committee, and a special advisory committee. Angela Silva-Bessa problematised the double standards for body donations and the handling of the dead before and after death, with a special focus on the cultural context of Portugal where the cultural practice allows for exhumation of burials as soon as 3 years after death – with teh assumption that the family cremates the remains or moves the remains to an ossuary. But the family is not always able to care for the remains, and they can also be donated to osteological collections. Silva-Bassa asked several important questions: Can this practice be better regulated? Should cemeteries have access to donation registers to be able to see if the person buried would object to being used in this way. Should there be another registry? Nichola Passalacqua and colleagues shared current American standards for forensic science.

Nicole Crescenzi getting ready to present at the Roundtable on illicit trade. Photo: Liv Nilsson Stutz

Ethcial Entanglements affilliate Nicole Crescenzi presented her work in a Round Table Session on illicit trade, where she focused on unforeseen ethical challenges of the new EAA recommendations to increase the use of 3D-copies of bones and other human remains. While this at first glance appears to be a convenient short cut around the growing critique against exhibiting authentic human remains, she argued, the technology itself opens up a whole new Pandora’s box of ethical issues, including ownership, control and reproducibility.