On July 25 (2023), the International Journal of Heritage Studies published (open access) the article “Between Objects of Science and Lived Lives. The legal liminality of old human remains” by Liv Nilsson Stutz, which is the first major article published for Ethical Entanglements. The article serves several purposes: 1) it presents a summary of the results from the survey of Swedish museums practices; 2) it reviews Swedish law with regards to the handling of different categories of human remains; and 3) it frames these analyses within the theoretical model that views human remains as moving along a spectrum between objects of science and lived lives – a theoretical foundation for Ethical Entanglements:

To capture the complexity of the category ‘human remains’, conceptually, legally, and scientifically, our research project ‘Ethical Entanglements’ relies on a model that sees them as moving on a spectrum between being objects of science and lived lives. This model is not intended to lead to any conclusion about how they should be handled, or define how we personally view them, but rather to capture the range of how they historically have been, and still are perceived, categorised, and handled – from the view of the remains as being a relative or an ancestor, to a view represented by the practice of predominantly scientific collection and curation – as objects to be studied. In between lies the range of levels of entangled object- and subjecthood that resonates through all the different aspects of the ethical challenge. Where along the spectrum, between object and subject, any given human remain is perceived to be located depends on several factors including provenance, research history, level of familiarity, level of information, state of preservation, and age, but also current political and cultural debates, cultural concerns, religious and spiritual convictions, and political needs.

The review of the legal instruments clearly demonstrates that there is a distinction made between the recently dead whose remains are covered by laws regulating medical practice, medical research, declaration of death, and burial – and old human remains, which are reduced to cultural heritage, often by proxy to remains resulting from living people’s actions – such as burials practices, commemorative practices, or ritual practices. The recently dead are viewed as subjects, the long dead as objects. But both researchers and the public know that it is not quite that simple.

In the front: The remains of a 7-year old child, with evidence of hypoplasia on the tooth enamel indicating stress related to food insecurity or possibly disease. In the back: a child cranium with healthy teeth. From the Nesolithic collective burial in Rössberga. Exhibition at the Swedish History Museum. Photo by Liv Nilsson Stutz. Intentionally blurred.

The article demonstrates that there is no real support in law, or in professional ethical guidelines that recognises this complexity, and this is a problem for several reasons:

“Are old human remains people, or are they heritage? How should they be treated in museums and research? While research practices, museum practices and public debates increasingly recognise the complex nature of old human remains as both objects of science and lived lives, this study shows that there is no consensus – neither in law nor in guidelines – on how to handle this development. The research on old human remains is a largely unregulated field. This is a problem for mainly two reasons: First, it leaves both museums and researchers working with old human remains vulnerable to critique from the public, especially from a post-colonial perspective questioning the right of research to treat the remains of people as objects of science. This critique is valid but can still be nuanced since many museum professionals and researchers share the sensibilities of human remains being a more complicated category than neutral objects. Second, the lack of standardised protocols for reviewing access to human remains for destructive sampling (Alpaslan-Roodenberg et al. 2021), and for sharing potentially sensitive data, risks causing unnecessary stress, potentially create conflicts, and in the worst case, may cause damage to valuable and sensitive remains.“

Nilsson Stutz, L. 2023: Between objects of science and lived lives. The legal liminality of old human remains in museums and research, Intl. Journal of Heritage Studies.

For the purposes of Ethical Entanglements a final challenge is viewed as central:

“…the review of both laws and practice identifies an inconsistency in the categorisation of human remains where old human remains from indigenous people are considered with more care for their subjectivity than human remains from non-indigenous contexts. This is a problem because it risks restricting the ethical debates to specific groups, while leaving other categories of old human remains completely unproblematized.”

Nilsson Stutz, L. 2023: Between objects of science and lived lives. The legal liminality of old human remains in museums and research, Intl. Journal of Heritage Studies.

The article proceeds to proposing possible ways forward of strengthening the professional ethics in the handling of old human remains in museums and research. Beyond new guidelines and legal frameworks, it is argued, we need clear processes that in turn will strengthen the ethical awareness within the field.

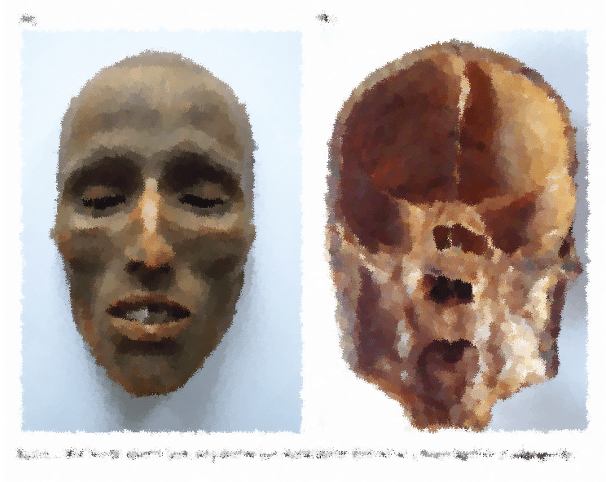

featured image: anatomical preparation showing a head with superficial musculature, and the nerves of the face. Exhibited at the University Museum in Groningen. Photo by Liv Nilsson Stutz (intentionally blurred).