After our visit in Amsterdam I continued to Groningen which aslo has an anatomical collection on display in its University Museum. Here, the anatomical collection is part of the exhibition on the history of the university and its scholars, and it is thus clearly inscribed in the broader history of research and scholarship. A separate room is dedicated for this purpose. The anatomical display is arranged on stepped shelves organised in a semi-circle, with mounted skeletons on top and with preparations of body parts and organs on the lower shelves. The room has a claire-obscure quality with dimmed lights and spots illuminating the white bones, and the body parts almost glowing through the amber coloured liquid of the old preparations. The display is accompanied by an interactive screen where visitors can see close-up photographs of each displayed specimen and read descriptions about pathologies and preparations. The exhibition is extremely interesting, quite moving, and, I must admit, very aesthetic.

The anatomical collection arranged on stepped semi shelves organised in a semi-circle. Photo by Liv Nilsson Stutz (intentionally manipulated)

On the opposite side in the same room, an exhibition is devoted to the contribution of Petrus Camper (1722-1789). Camper was Professor Medicinae Theoreticae, Anatomiae, Chirurgiae et Botanicae at the University of Groningen from 1763 and to his death. He was an academic celebrity of his time and a leading scholar in many fields, including comparative anatomy.

Tibout Regters – De anatomische les van Petrus Camper. Amsterdam Museum, Public Domain.

As part of his research, Camper studied the anatomical differences between humans and apes, in particular crania and larynxes. To address the context of this research, the museum signage both celebrates and problematises his legacy. The exhibition called “Bitterzoet Erfgoed” (Bittersweet Heritage) informs us that while Camper lived in a time of colonialism and slavery, he “did not accept this worldview” (i.e. slavery). That being said, the text continues “Camper’s work cannot be separated from colonial history,” as “he collected specimens (human and animal) from colonised regions including the skulls and skin specimens on display in this exhibition.” The next sentence sums up the central dilemma:

“This raises complex questions. We want to tell the story of Petrus Camper, but also treat the remains of people who did not choose to become subjects of scientific research with respect”

Text in the exhibition about Petrus Camper at the University Museum in Groningen.

Several human crania are on display in this part of the exhibition, and a color coded map indicates their provenance including Madagascar, Europe, Java, Russian Republic of Kalmykia, Angola, China, Jakarta, and Mongolia.

Display of skulls from different parts of the world. The crania wee collected by Camper for his research into comparative anatomy. Photo: Liv Nilsson Stutz, intentionally blurred.

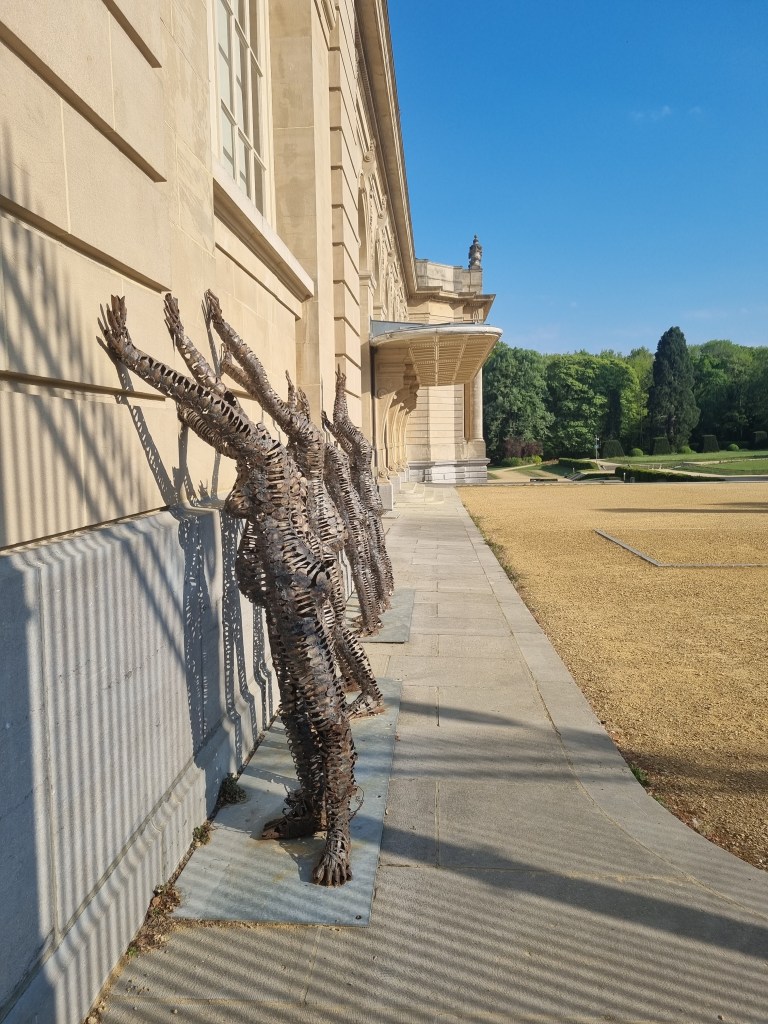

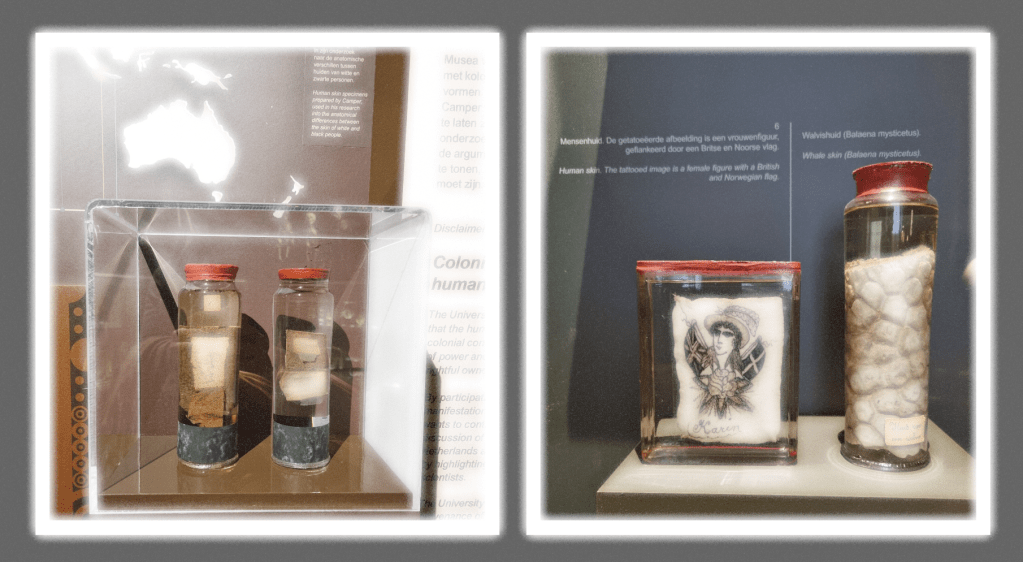

The transparent and honest way in which the exhibition communicates about the content of the collections and their problematic history, is interesting and quite admirable. The display of remains such as skin samples brings the hot button topic of racism into focus. The exhibition strikes the balance between communicating that while Camper’s research was not seeking to support racism as an ideology and a “scientific” concept, he still worked within a context of colonialism and othering. And while not explicitly stated, the knowledgeable visitor can probably fill in the blanks as to how this research tradition came to be enmeshed with race science only a few generations later. While taking risk with this display, the museum paradoxically takes responsibility for its collections as it does not try to avoid confronting difficult issues or hide its collections.

Skin samples on display in the museum. To the left, skin samples form humans from different parts of the world, displayed in the Bittersweet Heritage exhibition. The samples were used by Camper to understand human variation between white and black skin. To the right, human tattooed skin (the face of a woman and the British and Norwegian flags) exhibited with the skin of whale to illustrate Camper’s work in comparative anatomy. Photos by Liv Nilsson Stutz, intentionally blurred.

Interestingly (and typically) the problematisation is limited to the anthropological research and exhibition, and does not discuss the medical collection displayed only a few meters away in the same room. The context of the “bitter sweet heritage” is not extended to include collection practices from other contexts (such as, presumably, maternity wards and other care facilities). This relates to a more general pattern that we can see in how different categories of human remains sometimes are treated with different consideration and levels of problematisation.