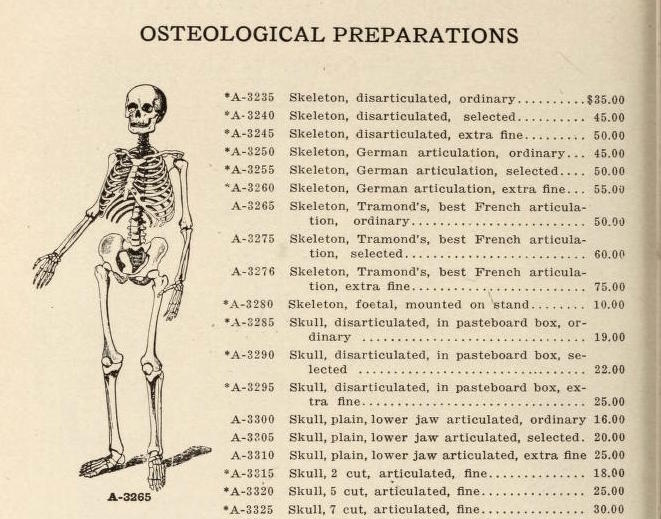

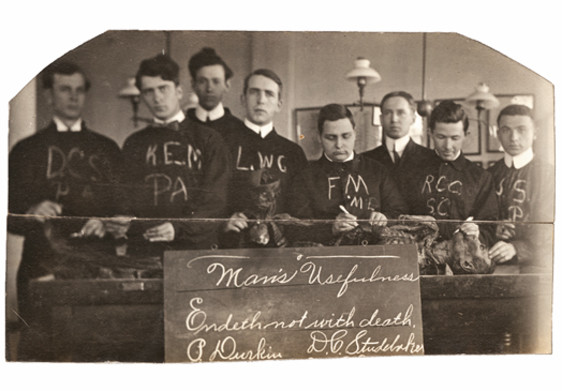

Last week it was that time again. Swedish media and the public were made aware of the presence of human remains in schools across Sweden. This time the event that triggered the news coverage was the discovery, on behalf of a parent, that a skeleton suspended from the roof of a theatre stage in their child’s highschool in Danderyd as a Halloween decoration, might in fact be authentic. It is interesting to note that nobody at the school seems to have been aware of its existance (including the biology teachers), and nobody was able to authenticate the skeleton as human.

After the discovery, the display was removed, and the school started an investigation that consulted an outside specialist. After examining the remains, the specialist could confirm: these were the remains of a human. But since the consultation was only osteological, its provenance remained unknown. It would require a lot more work to trace who the person whose bones were examined had been in life. This is not unusual. Typically, human remains in schools have a long and complex history that is poorly documented and often forgotten. They were acquired many decades ago, and may have circulated between collections, and changed schools. The Danderyd Highschool now faced the same problem that many Swedish schools have faced before: what should they do with these remains?

As I have argued in the article Between Objects of Science and Lived Lives. The legal liminality of old human remains, human remains from historic contexts are situated in a legal gray area, and there are no clear laws on how to handle them. For any school that suddenly discovers that they have human remains in their closets, it is difficult to know what the right thing to do might be. They can turn to the police, to museums, to the National Heritage Board, and even to the Swedish Church – and many do, and find that not only do these institutions not feel that this is their business, but also that nobody can really advise them about what to do. This conundrum has been discussed in this blog before, and the case of schools has also been the subject of excellent reporting by Swedish Radio in 2016.

“What is well intentioned may still be ill advised.”

In the case of the Danderyd skeleton, the decision has now been made that it will be cremated and buried in the local cemetery. While this, at first glance seems to be a well intended course of action, it is highly problematic since no provenance research has been carried out on the remains and we therefore have no idea if this would be desired or even acceptable for this individual. What is well intentioned may still be ill advised. To put it bluntly, this act is more about satisfying the needs of the school and the local community than the needs of the person whose remains were used as a prop by that very same community only a few weeks ago. This is not good enough.

In several interviews with Swedish Radio and TV I have argued that given that there is likely to be a large amount of human remains in Swedish schools, this is not a problem that is likely to go away anytime soon. What we need is a proper inventory of what is out there, so that we can get an overview – not unlike the inventory that was carried out in Swedish museums in 2016. Once we have an overview we can develop support and guidelines. Ideally, provenance research should also be carried out so that we know what any appropriate course of action might look like.

This is a big job that will require specialist competence. It is not fair to expect individual schools to take responsibility for this. The situation in Sweden is complicated by the fact that the administrative responsibility of schools has been decentralised from the state to the county level (kommun) in a reform in 1991. Is is safe to say that the large majority of the human remains in Swedish schools were acquired long before then, and the responsibility of this necessary inventory and research must therefore fall upon the Swedish state and in particular on the National Agency for Education (Skolverket). When confronted with this request from me in a TV interview on Nov 15, the National Agency for Education predictably punted the question to the county levels, who in turn decided not to respond to the journalists requests.

What happens next will be interesting to follow, and while the future is unpredictable, one thing is for sure: if we do not take responsibility for this problem now, we will have another story just like this one break in a couple of years, and we will start the debate over. Again.

Update: Liv Nilsson Stutz published a short text in Swedish on the topic in Bi-lagan, a resource publication for biology teachers in Swedish schools, published by Uppsala University, in the fall of 2024.

featured image: “Vintage Halloween costume snapshot” by simpleinsomnia is licensed under CC BY 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/?ref=openverse.