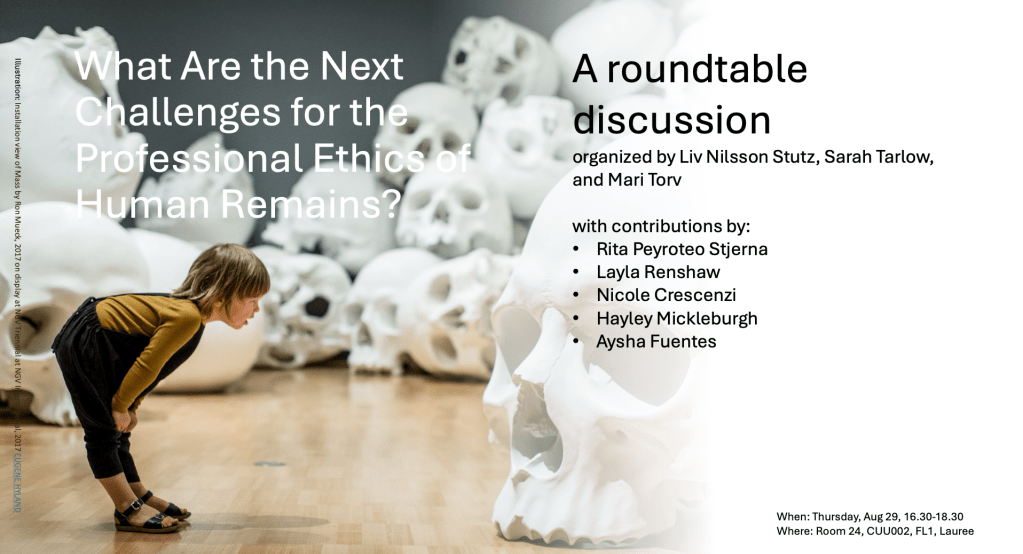

At the annual meeting for the Association for European Archaeologists at Sapienza University in Rome, August 28-31, 2024, Ethical Entanglements organised a roundtable discussion called “What are the Next Challenges for the Professional Ethics of Human Remains.” It might be relevant to note that when we submitted the proposal for the conference we were asked to merge with another session on ethics in biomolecular archaeology. We were happy to do this, but the fact that only two proposals to this year’s conference were focused on professional ethics is somewhat concerning. For perspective: this conference allegedly had 5000 delegates and, from a glance through the abstract book, over 1000 sessions (!). A keyword search of the final program revealed that this was indeed the only session devoted to ethics that ended up in the final program. Are we really, as a field, done with ethics? Are we fed up, or is the problem really considered to be solved?

To stimulate discussion and a freer from of exploration, we opted for a round table format this year instead of a regular session. The panel consisted of current and former members of the Ethical Entanglements team and invited speakers who in different ways have inspired our work in the past years:

Rita Peyroteo Stjerna, is an archaeologist of death and bioarchaeologist, and member of the Ethical Entanglements team where her research is focused on the ethics of the biomolecular dimension of human remains research. Her current affiliation is Linnaeus University and its Center for Colonial and Postcolonial Studies called Concurrences.

Layla Renshaw, Assistant Professor at Kingston University, UK, is specialised in the combination of forensic science and social science in her interdisciplinary research on mass graves, post-conflict contexts and Human Rights investigations. Her background brings unique perspectives on ethics, ranging from the political implications of the past, of memory, and loss in post-conflict contexts, to medical ethics in forensic science.

Hayley Mickleburgh, is an Assistant Professor at the University of Amsterdam. She is an archaeologist and biological anthropologist with a focus on archaeothanatology, forensic science, sensory archaeology, and digital archaeology. Hayley was part of the original Ethical Entanglements team, and her experience in forensic science has been an important inspiration for developing ideas that overlap with medical ethics and ethics of care.

Ayesha Fuentes, is an objects conservator at the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, with a special interest in Asian material religion including the use of human remains in objects, and the ethics of museum practice. Her profile brought a much needed perspective from the museum side, but also an original understanding of the use of human remains as meaningful components of material culture.

Nicole Crescenzi, is a Ph D student at IMT Lucca, Italy. Her work investigates the care for human remains in museums with a focus on the experience of the public of the exhibition of human remains. Nicole is a member of Ethical Entanglements as she has become integrated into the group as a guest researcher and PhD student.

The discussion was led by Liv Nilsson Stutz and Mari Torv –archaeologist of death and bioarchaeologist at the University of Tartu. Mari has been instrumental in taking the initiative to form an ethics group at ISBA (the International Society for Biomolecular Archaeology).

The purpose of the roundtable was to provide a space for open exploration of emerging ethical challenges. The conversation started out with the specialist perspectives represented by the panel, but also engaged the audience. The discussion was future oriented and structured in three themes:

The first segment, New tools, New Practices explored how the very definition of human remains is changing rapidly with new research methods including biomolecules (including DNA, isotopes, etc), 3D-scanning and reproduction, and how new practices such as Open Science require completely new ethical considerations. It was pointed out that while some of these challenges are not entirely new (museums have long curated potentially sensitive photographs of human bodies), the current development calls for a more robust approach to the ethical challenges. We also noted that while we are aware of the problems we do not yet have any solutions to this issue, and the field keeps moving ever faster.

The discussion explored different options of solutions for museums, including community engagement, and repatriation. But it was also asked: is it not our professional duty to make museums a safe space for human remains?

A second segment, New Awarenesses, New Sensibilities started by discussing categories of vulnerablilities that are not often considered in the debate framed mostly by the postcolonial critique. Hayley Mickleburgh shared the example of a collection of crania from an orphanage in Amsterdam. How can we best care for the remains of these often very young and marginalised girls from 19th century? The discussion explored different options of solutions for museums, including community engagement, and repatriation. But it was also asked: is it not our professional duty to make museums a safe space for human remains? A topic that was further explored by Nicole Crescenzi and Liv Nilsson Stutz in a regular paper in a museum oriented session the following day.

Another significant theme broached in this segment was the disciplinary legacy of violence that permeates biological anthropology. Many of the methods and teaching materials we use today, and that have made their way into the disciplinary practice, were developed within a space of violence. How do we as a discipline address this legacy?

In a final segment called New Audiences, New Access the discussion focused on teaching and social media. Many raised the concern that despite the fact that the disciplines of archaeology and biological anthropology are clearly both aware of their ethical complexities, we still have a very limited engagement with these issues in universities across Europe. Teachers struggle with the difficult challenge of providing meaningful, engaging, and long term learning opportunities for students with limited time to cover more and more material. All agreed that it is important to include ethics continuously through the process, but all also struggled with how to make this happen in an increasingly austere university context. At this point the audience, who had been impatiently waiting, started to spontaneously participate and we decided to open up the floor for discussion.

Despite the late hour of the day (16.30-18.30), the sweltering heat of Rome in August (35°C), and the limited air conditioning in the room, the audience was active and engaged in brilliant conversation. Among the interesting points made in the audience I noted Sofia Voutsaki’s (Professor of Greek Archaeology at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands) point about how ethics can be weaponised, and that we need to be aware of that dimension in our work as well. On a related topic, Megan Perry (professor of anthropology at East Carolina University, USA) discussed the difficulties of a one size fits all approach to what it means to be ethical. What do you do, she asked, if you work in a region where community engagement is difficult simply because the community is not really that interested? Does that mean that you are not being ethical, or do you need to force something just to qualify as “ethical”? (I paraphrase). And if you do – is this not unethical?

It was also suggested that we may underestimate how much we as archaeologists and biological anthropologists actually engage with professional ethics. One voice in the audience pointed out that we in fact have a robust reflective literature, that at least makes us aware of the issues, in particular regarding the political dimensions of our field. I agree to an extent. It is true that archaeologists and anthropologists for decades have engaged with their disciplinary history, and, to some degree, professional ethics – perhaps more than colleagues in other disciplines with whom we now often collaborate.

I agree that as a field we have a tradition of being reflexive and we have resources and tools to act ethically. But even so, what is lacking, in my opinion, is a deeper and more critical engagement with ethics. One that is not limited to a list of “what not to do,” but consists of a thoughtful reflective attitude that engages professional ethics as dynamic and ongoing practice. One that keeps conversations like the one we were having in that room going, allowing the reflexivity to permeate our professional practice.

A good illustration of this was an audience member working with DNA analysis. He shared that as a biologist he had received no training in the history of his discipline. In comparison, it would seem that archaeology, museology, and anthropology are doing OK. I agree that as a field we have a tradition of being reflexive and we have resources and tools to act ethically. But even so, what is lacking, in my opinion, is a deeper and more critical engagement with ethics. One that is not limited to a list of “what not to do,” but consists of a thoughtful reflective attitude that engages professional ethics as dynamic and ongoing practice. One that keeps conversations like the one we were having in that room going, allowing the reflexivity to permeate our professional practice.

When the session ended at 18.30 we left the room, not only with more questions (being a cliché it is also often true), but also with the feeling that the field is buzzing with energy and desire to discuss and explore these issues, and the realisation that with colleagues like the ones in this room, from all across Europe and the US, and from a range disciplines, we are making progress toward more reflective professional ethics. The engagement, the willingness to explore and to share that characterised the discussion constituted a stark contrast to the lack of formal opportunities to do so at this conference. But while I initially had wondered if the field is fed up with ethics–if we are “done”–my worries were proven unfounded. Leaving the room that warm evening I could not help but thinking – yes, there is a lot of work to do, but we will be OK.