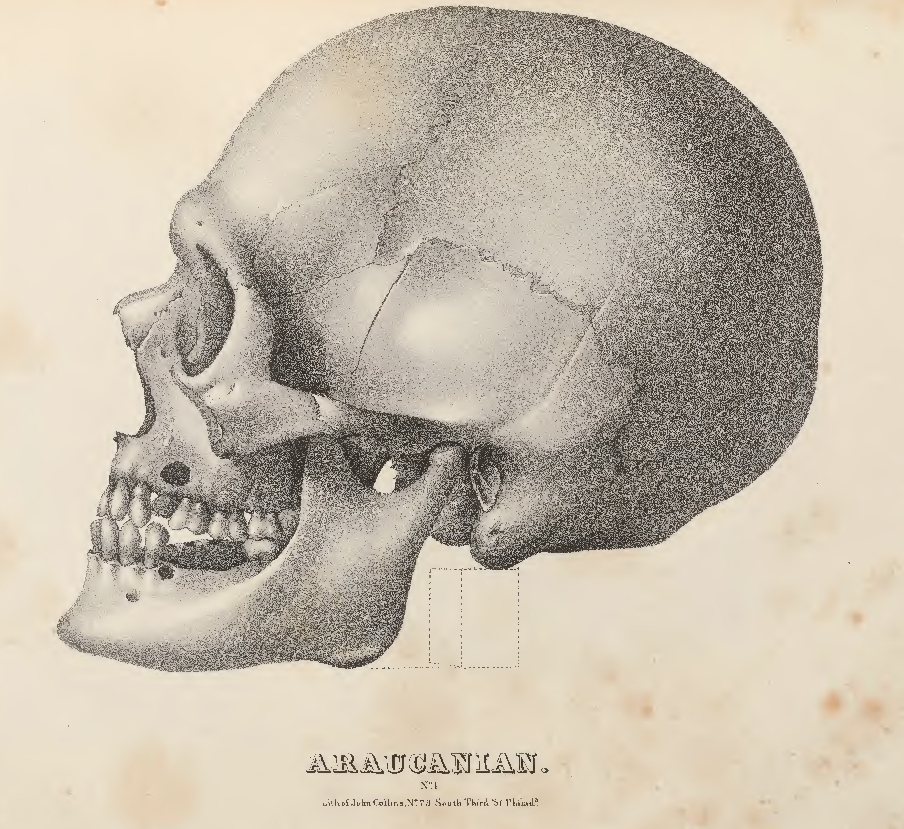

On April 12, 2021, The Morton Collection Committee released a report on their work of examining the ongoing issues relating to the anatomical collection created by Samuel George Morton (1799-1851), physician, natural scientist, renowned polygenist, and originator of the American School of Anthropology. Morton built a collection of 900 crania to provide “hard evidence” for the superiority of the white race, primarily by measuring the volume of the crania, linking the size of the brain to intellectual ability. The work was published in a series of volumes of which Crania Americana (1839), and Crania Aegyptica (1844) are the most well known. Both are renowned for their detailed drawings of the crania (see below), and both publications used the collection to demonstrate the alleged superiority of the “Caucasian race.” The collection is deposited at the Penn Museum since 1966, and it is now time, the report states, to take responsibility for this collection including developing a process for the repatriation of remains to descending communities.

Morton’s studies have been critically discussed by Stephen J. Gould who argued that they were plagued by implicit bias. This study, and Morton’s implicit bias in general have subsequently been discussed by J. E. Lewis et al., Michael Weisberg and Diane B. Paul, and Paul Wolff Mitchell , and while there is scholarly disagreement on the level of “fudging” in the study, there is a general consensus that Morton’s work was underpinned by the racist doctrine of polygenism, and that his ultimate conclusions as well as his casual remarks throughout the texts were openly racist. His work must also be understood in a context in which it provided scientific evidence that supported the American colonial effort, including attempts to eradicate and marginalise the Native Americans, and the economic system relying on both the transatlantic slave trade and on the labour of enslaved people.

Like so many other anatomical collections, the Morton collection has a complex history. Morton initially collected 900 crania, and after his death in 1851, the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia bought and expanded the collection to ca 1.300 specimens. It was moved to the Penn Museum in 1966. We are familiar with similar transitions of historic collections from medical faculties to history museums (e.g. the anatomical collection transfered to the Lund University Historical Museum in 1995, and collections transferred to Gustavianum in Uppsala in 2009 and 2011, etc). When they are transfered to these museums – they are, in many ways, already a part of our history, being the cultural artefacts of a dark heritage of science. However, the fact that these collections are historical does not automatically neutralise them, and they remain both valuable and problematic. Since 2002 the Morton collection has been extensively scanned (over 17.500 CT scans have been distributed to researchers across the world), and the collection has continued to be used for research (source: PennMuseum/The Morton Cranial Collection).

While the collection had been known and debated as problematic for a long time, it appears that the situation came to a tipping point in the summer of 2020. In the report, the Morton Collection Committee clearly states that it was the events following the police killing of George Floyd on May 25, 2020 and the continuously growing influence of the Black Lives Matter movement and renewed calls for racial justice that prompted the institution to critically examine its history and reevaluate its relationship to the Morton collection.

In the US context, and for researchers who are familiar with the impact of the the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act on archaeological collections there since 1990, it seems almost strange that it took this long for the museum to “reassess its practices of collecting, storing, displaying, and researching human remains” and to provide “a visitation location for human remains that provides a quiet, contemplative space for reconnections and consultation visits in its future plans for rehousing the collections.” But this also demonstrates to what extent our practices are shaped by existing guidelines and legal frameworks, and how remains that are not explicitly subject to these have been able to remain more or less unaffected by the developments in other areas of museum practices with regards to human remains. However, it is also clear that the experience from engaging with NAGPRA over the past 30 years has been valuable as the museum develops practices to handle the current situation. It will be interesting to follow this development as a case study for how human remains in these complex and problematic anatomical collections may be curated and returned in the future.

As this work progresses, we must also remain engaged in continuing to examine how the engagement with these collections is shaped by current events, and assure that remains that are not illuminated by the limelight of current political debates are not forgotten. In addition, we should also ask to what extent new technology, like CT scanning, provides new solutions to old problems, or perhaps creates new problems and new ethical frontiers to examine.